Many governments and donor agencies have been investing in early childhood mortality reduction and health programs in order to meet the Millenium Development Goal (MDG) of reducing child mortality to 1/3rd of what it was in 1990. Has it made a difference? How did countries do? What interventions worked best? These are basic questions that are quite difficult to answer. Nevertheless, an international team of researchers evaluated such programs for the years 2000-2014, and it shows the world has made tremendous progress in saving children’s lives. What is more, they have defined a process to make it easier to perform such evaluations going forward.

The report was published jointly by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington and the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for Financing the Health Millennium Development Goals and for Malaria.

According to the analysis, which was published in the UK medical journal The Lancet in July 2015, lives of over 34 million children have been saved between 2000 and 2014, at a relatively low cost. Depending on a country’s income level, the costs can vary from $4,205 (Rs2.5 lakh) per child in low-income countries to $10,016 (Rs6 lakh) in upper-middle-income countries. In India the estimated cost is $6,500 (Rs3.9 lakh) per child.

Over the 15 year period, the overall amount spent by low- and middle-income country governments was $133 billion (Rs8 lakh crore) on child healthcare. The researchers calculated that these governments managed to save around 20 million children. Private and public donors, most of these from high-income countries, spent over half that, $73.6 billion (Rs4.4 lakh crore), and saved about 14 million children. External donors got more results for their money because they invested in poorer countries where the costs of saving a child are lower.

“You can spend $4,000 on many different things, but there are very few places where the money would deliver the kind of impact you get by investing it in child health,” said Christopher Murray, IHME Director. “If you invest in the poorest countries, you will see the biggest impact in child health because the costs of things like nutrition programs, vaccines, and primary care are lower.”

In order to develop the scorecard, the researchers analyzed funds spent by governments and donors such as USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, World Bank and UNICEF. The scorecard should let governments, policymakers and donors compare data across nations.

“We believe that this scorecard can and should be used after the end of 2015 to aid in tracking progress on the Global Goals for Sustainable Development,” said Ray Chambers, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for Financing the Health Millennium Development Goals and for Malaria. “We know that despite the efforts of governments and donors to improve health in low-income and middle-income countries, too many children die before the age of 5. Without a way to monitor and publicly share progress regularly, we will miss the opportunity to build on the momentum we have seen since the Millennium Declaration.”

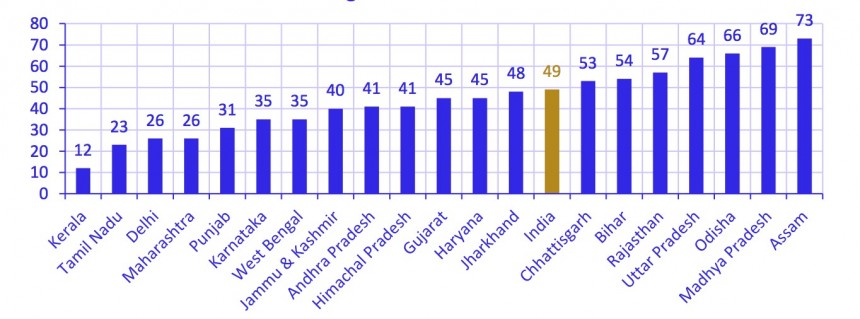

Perhaps in India the scorecard could be used for states as well. The under 5 mortality rate in India was an estimated 125 per 1000 live births in 1990. The MDG target for the end of 2015 is 42. According to the Indian government’s estimate at the beginning of 2015, the rate is expected to be 48 at year’s end, coming close to the target. However, this national average hides a wide variance among the states. The scorecard may help in identifying what states such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu are doing well and what states such as Assam and Madhya Pradesh need to change.

Under 5 mortality rates in 2013 for several large states. Source: Millenium Development Goals India Country Report, Government of India.

Share your thougths, leave a comment below. Please like FamiLife’s page on Facebook so that you get all our articles and others may find us.